At MayaData we like new tech. Tech that makes our databases perform better. Tech like lockless ring buffers, NVMe-oF, and Kubernetes. In this blog post we’re going to see those technologies at work to give us awesome block storage performance with flexibility and simple operations.

Mayastor + SPDK + NVMe = fast databases

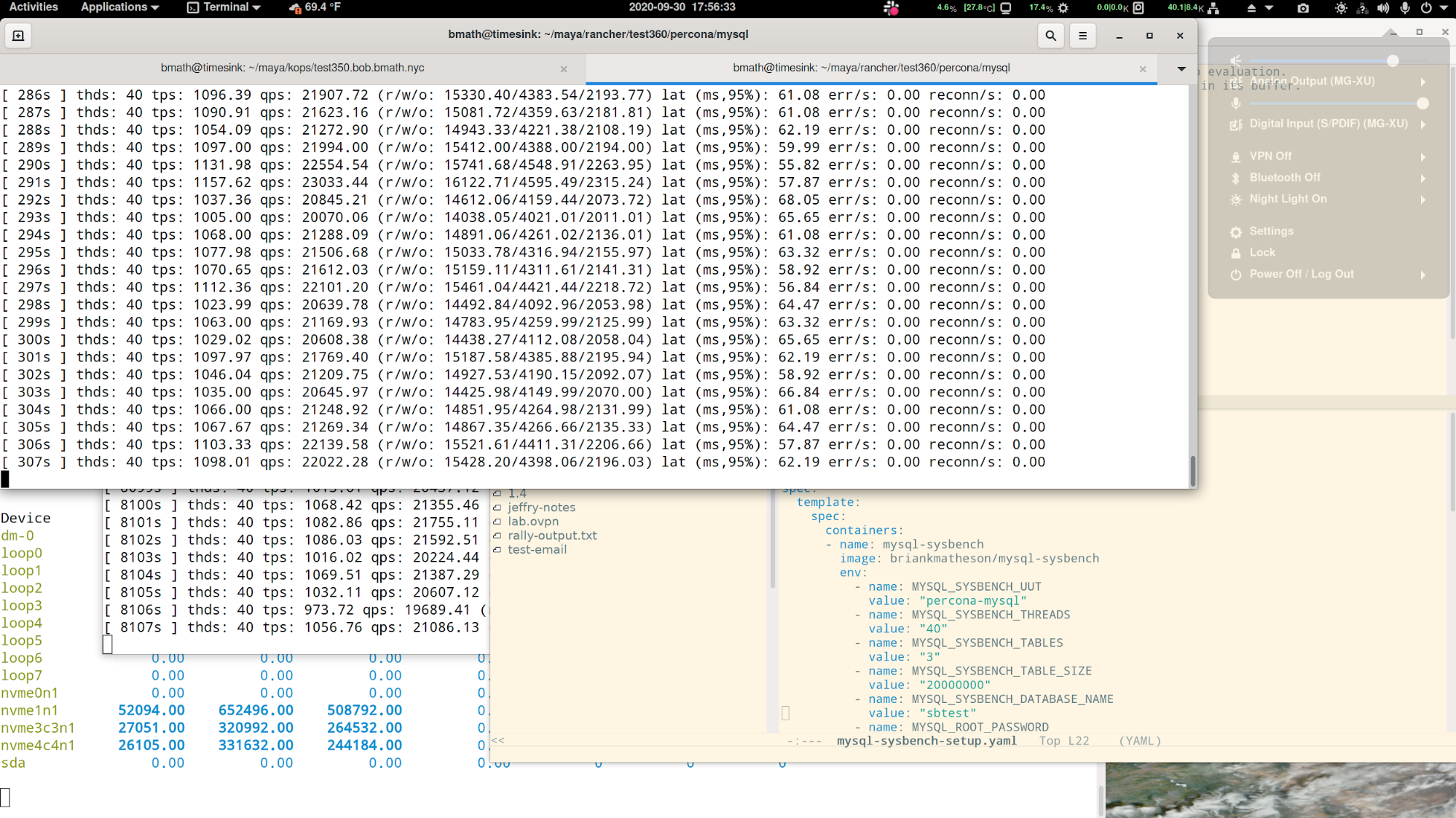

Mayastor is new tech, it’s fast, and it’s based on SPDK. Why is SPDK exciting? It’s a new generation in storage software, designed for super high speed low latency NVMe devices. I’ll save you the scrolling and just tell you I believe Mayastor was able to max out the practical throughput of the nvme device I used for my benchmark, allowing for multiple high performance (20kqps+) database instances on a single node. Perfect for a database farm in Kubernetes

Why Test With a Relational DB?

Open source relational databases are a staple component for app developers. People use them all the time for all kinds of software projects. It’s easy to build relationships between different groups of data, the syntax is well known, and they’ve been around for as long as modern computing. When a dev wants a relational database to hack on, odds are good that it’s going to be Postgres or MySQL. They’re Free. They’re open source. They’ve both been quite stable for a long time, and they both run in Kubernetes just great. The good folks at Percona make containerized, production ready versions of these databases, and we’re going to use their Percona Distribution for MySQL for the following tests.

Kubernetes and the Learning Curve

DBs are Often IO Bound

The trick is, databases are notoriously disk intensive and latency sensitive. The reason this has an impact on your Kubernetes deployments is that storage support in stock settings and untuned K8s clusters is rudimentary at best. That’s created a number of projects that are out to provide for storage in K8s projects, including, of course, the popular OpenEBS project.

---

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: percona-mysql

labels:

app: percona-mysql

spec:

replicas: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: percona-mysql

template:

metadata:

name: percona-mysql

labels:

app: percona-mysql

spec:

nodeSelector:

app: db

securityContext:

fsGroup: 1001

containers:

- resources:

limits:

cpu: "20"

memory: 8Gi

name: percona-mysql

image: percona

args:

- "--ignore-db-dir"

- "lost+found"

env:

- name: MYSQL_ROOT_PASSWORD

value: foobarbaz

ports:

- containerPort: 3306

name: percona-mysql

volumeMounts:

- mountPath: /var/lib/mysql

name: percona-mysql

volumes:

- name: percona-mysql

persistentVolumeClaim:

claimName: vol2In this post I’m going to investigate the newest of the storage engines that comprise the data plane for OpenEBS. As a challenge, I’d like to be able to achieve 20,000 queries per second out of a MySQL database using this storage engine for block storage underneath.

Now, getting to 20kqps could be easy with the right dataset. But I want to achieve this with data that’s significantly larger than available RAM. In that scenario, 20kqps is pretty fast (as you can see below by the disk traffic and cpu load it generates).

There are a number of great options available for deploying MySQL in Kubernetes, but for this test we really just want a good, high performance database to start with. I won’t really need fancy DBaaS functionality, an operator to take care of backups, or anything of the sort. We’ll start from scratch with Percona’s MySQL container, and build a little deployment manifest for it. Now, maybe you’re thinking: “don’t you mean a stateful set?” But no, we’re going to use a deployment for this. Simple and easy to configure alongside of Container Attached Storage.

The deployment pictured references an external volume, vol2. Now we could create a PV for this on the local system, but then if our MySQL instance gets scheduled on a different machine, the storage won’t be present.

Enter Mayastor

---

kind: PersistentVolumeClaim

apiVersion: v1

metadata:

name: vol2

spec:

storageClassName: mayastor-nvmf-fast

accessModes:

- ReadWriteOnce

resources:

requests:

storage: 20GiMayastor is the latest storage engine for OpenEBS and MayaData’s Kubera offering. Mayastor represents the state-of-the-art in feature-rich storage for Linux systems. Mayastor creates virtual volumes that are backed by fast NVMe disks, and exports those volumes over the super-fast NVMf protocol. It’s a fresh implementation of the Container Attached Storage model. By CAS, I mean it’s purpose built for the multi-tenant distributed world of the cloud. CAS means each workload gets its own storage system, with knobs for tuning and everything. The beauty of the CAS architecture is that it decouples your apps from their storage. You can attach to a disk locally or via NVMf or iSCSI.

Mayastor is CAS and it is purpose built to support cloud native workloads at speed with very little overhead. At MayaData we wrote it in Rust; we worked with Intel to implement new breakthrough technology called SPDK; made it easy to use with Kubernetes and possible to use with anything; and open-sourced it because, well, it improves the state of the art of storage in k8s and community always wins (eventually).

If you’d like to set up Mayastor on a new or existing cluster, have a look at: https://mayastor.gitbook.io/introduction/

The Speed Hypothesis

The first thing I want to do is get an idea of how many queries per second (QPS) at which the DB maxes out. My suspicion at the outset is that the limiter for QPS is typically storage latency. We can deploy our Mayastor pool and storage class manifests in a small test cluster just to make sure they’re working as expected, and then tune our test to drive the DB as hard as we can. Performance characteristics of databases are very much tied to the specifics of the workload and table structure. So the first challenge here is to sort out what kind of workload is going to exercise the disk effectively.

Sysbench is a great tool for exercising various aspects of Linux systems, and it includes some database tests we can use to get some baselines. https://github.com/akopytov/sysbench is where you can find it. We can put it in a container and point that mysql OLTP test right at our database service.

After a little bit of experimentation with sysbench options to set different values for the table size, number of tables, etc., I arrived at very stable results on a small cluster in AWS using m5ad.xlarge nodes. I’ve settled on 10 threads and 10 tables, with 10M rows in each table. With no additional tuning on MySQL, sysbench settles into about 4300 queries per second with an average latency at 46ms. Pretty good for a small cloud setup.

With that as a baseline, let’s see how much we can get out of it on a larger system. Intel makes high core-count cpus and very fast Optane NVMe devices, and they’ve generously allowed us to use their benchmarking labs for a little while for some database testing. Without going into too much hardware geekery, we have three 96 core boxes running at 2.2Ghz with more RAM than I need and 100Gb networking to string them together. Each box has a small Optane NVMe device, and this single little drive is capable of at least 400k iops and 1.7GB/s through an ext4 filesystem. That’s fast. The published specs for this device are a little bit higher (about 500k iops and 2GB/s) but we’ll take this to be peak perf for our purposes.

Results of the First Test

For the first test, just to characterize the setup, I threw 80 or so cores at the database, and ran sysbench against it with a whole lot of threads. Like 300.

I started with a smaller table size just to save a little time on the load phase. It took a few iterations to get the test to run - adjustments to max_connections. The smaller table size means it might fit into memory, but it’ll test our test framework quickly. Sure enough, running our OLTP test gets us close to 100k queries per second. But, there’s no real disk activity. We need more data in order to test the underlying disks.

I cranked up the table size to 20,000,000 rows per table, tuned Mayastor to use three of the cores on each box, and started tuning the test to get max queries per second out of it. Three tables seem to be enough to overflow the 8G of RAM we have allocated to the container. Now when I check the disk stats on the node, there’s plenty of storage traffic. Still less than a gigabyte per second though. The system settles down into a comfortably speedy 30kqps or thereabouts, with disk throughput right around 700MB/s and a latency right around 50ms per query. Curiously the database is using about 8 cores. Clearly we don’t need to allocate all 80.

We’ve seen more than 700MB/s out of the storage already from our synthetic tests. That’s pretty far off of the peak measured perf of 1.7GB/s.

I wonder if we can get another MySQL on here…

Sure enough, this system is fast enough to host two high performance relational database instances on the same nvme drive, with cpu to spare. If only I had another one of those NVMe drives in this box….

That’s about 1.1GB/s, with 52k IOPs. Not bad. We might even be able to fit a third in if we’re willing to sacrifice a little bit of speed across all the instances.

There’s more work to be done to characterize database workloads like this one. There’s also an opportunity to investigate why the database scales up to 20-30k IOPs but leaves some storage and system resources available.

Perhaps most importantly - Maystor provides a complete abstraction for kubernetes volumes, and allows for replicating to multiple nodes, snapshotting volumes, encrypting traffic, and generally everything you’ve come to expect from enterprise storage. Mayastor is showing the promise here of LocalPV like performance - at least maxing out the capabilities of our DB as configured - while also providing the ease of use and ability to add resilience.

Lastly, if you are interested in Percona and OpenEBS, there are a lot of blogs from the OpenEBS community and a recent one by the CTO of Percona on the use of OpenEBS LocalPV as their preferred LocalPV solution here: https://www.percona.com/blog/2020/10/01/deploying-percona-kubernetes-operators-with-openebs-local-storage/

The Percona Community Forum, OpenEBS, and Data on Kubernetescommunities are increasingly overlapping and I hope and expect this write up will result in yet more collaboration. Come check out Check out Mayastor on your own and let us know how Mayastor works for your use case in the comments below!

Brian Matheson has spent twenty years doing things like supporting developers, tuning networks, and writing tools. A serial entrepreneur with an intense customer focus, Brian has helped a number of startups in a technical capacity. You can read more of Brian’s blog posts at https://blog.mayadata.io/author/brian-matheson. ∎

Discussion

We invite you to our forum for discussion. You are welcome to use the widget below.