Tarantool is an application server and a database. The server part is written in C, and the user is provided with a Lua interface to use it. Then, Tarantool is an open-source product with its source code in open access, and anyone can develop and distribute Tarantool-based software freely.

Today, I’m going to tell you about an attempt to write my own data structure for the search (the Z-order curve) and build it into the Tarantool ecosystem.

I work as a developer in the Tarantool Solution Team. I don’t create Tarantool but use it extensively. For me, this is an experiment — an attempt to figure out how Tarantool works at a lower level.

What is Tarantool, and where does it store data?

Tarantool is known as an in-memory database (though we have an engine for disk storage too). Engine memtx allows you to store all your data in random access memory and satisfies all ACID principles at the same time.

The equivalent of relational tables in Tarantool is space where tuples are stored. Unlike relational tables, tuples in space can generally have an optional length. Physically, they are stored in a search data structure, with the search key — primary key — is always unique.

Supplementary structures can be built too, i.e. secondary indexes that store only a pointer to a tuple. A secondary index can be not unique, but this is only observable behavior visible to the user. Any index that is not unique is added with primary index fields by default. This way, the stability of tuple sorting inside the index is ensured.

Tarantool supports different types of indexes:

- Firstly, it is B-Tree (B+*-Tree, to be exact). Quite a lot has been written about the structure of [B-Trees]. I would only note that data is stored in a sorted form, making it possible to search by indexed key prefix.

- Index based on a hash table. It will suit you if you don’t need interval selections. The access is by full key. Unlike B-Tree, the time of access to an element is constant, not logarithmical. This index is always unique.

- R-Tree. This type of index is more specialized. It is intended for storing “multidimensional” data, i.e. geographical coordinates. It supports indexing for fields of only one type: array. This is the array of our false coordinates which are ordinary floating-point numbers. It enables search for points located both within and outside a specified border, as well as the nearest neighbors.

- Bitset. It is intended for storing bit arrays in spaces and fulfilling requests using bitmasks.

Z-order curve, or Morton curve

Where the idea to write my own index, a rather exotic one, came from?

Once I stumbled upon Amazon articles [1, 2] telling about the Z-order curve, or Morton curve, structure. This is a scheme for arranging “multidimensional” data inside a flat structure (Z-order curve), which is then fitted into B-Tree. This should help avoid total data scanning. Generally, information about any object having a set of characteristics can be considered multidimensional data. For example, an individual’s height, weight, shoe size, etc. R-Tree is used for this purpose in most databases.

A little bit about how the Z-order curve works.

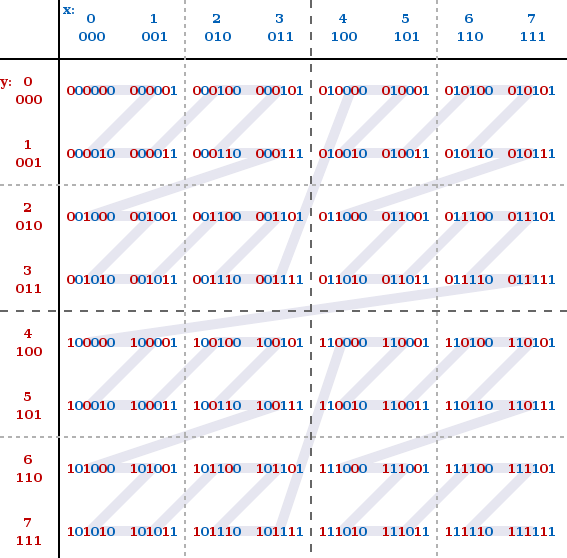

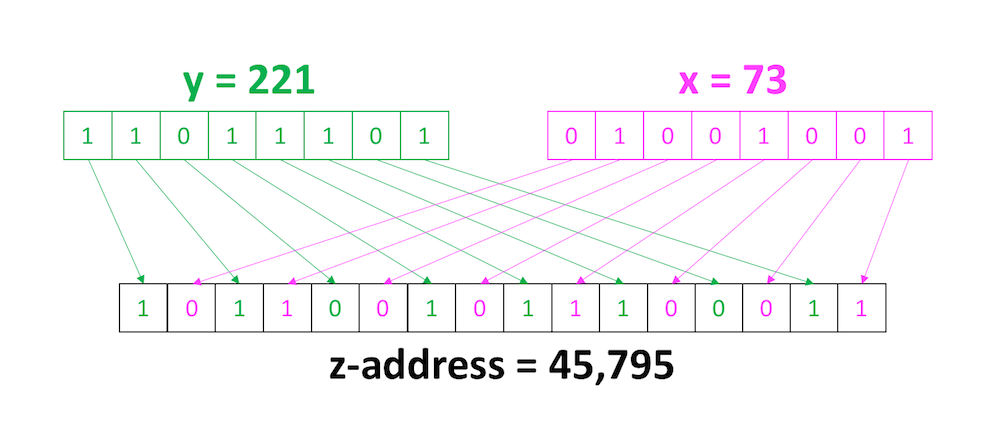

The Z-order curve, or Morton curve, is obtained by interleaving bits of a point’s space coordinates. Z-addresses obtained this way have the property of locality. Points that were adjacent in multidimensional space would normally be located next to each other in projection to a flat line as well.

Schematically, interleaving looks like this:

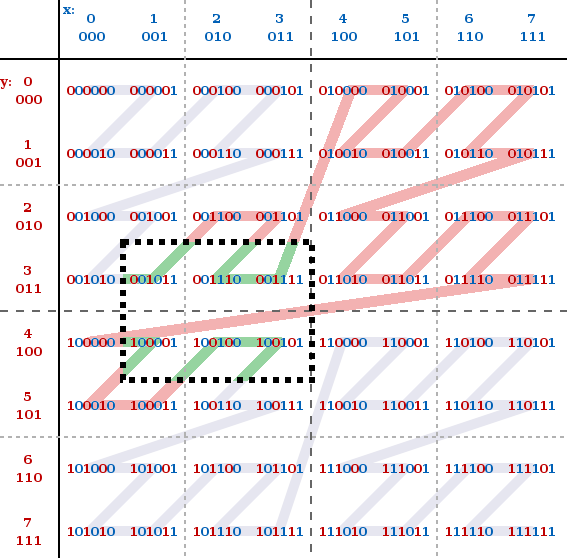

How does it work? We delimit a region in space — hypercube (rectangle, if in two-dimensional space) — using two points located on a diagonal. They are projected on two points on a straight line. And then we see an unpleasant side effect: some points are outside the delimiting rectangle.

That is, we can’t just iterate with this curve. Fortunately, we can “jump” back to the search area using a special algorithm when we exceed the limits. As soon as we go beyond the end point of the curve (let’s call it upper_bound), the search is over.

In the case of B-Tree, we would have a set of intervals, and sequential scanning of B-Tree would start upon such request. This does take quite a lot of time in the case of a large data set.

There were other publications about this curve that heated up my interest. For example, those about how it was integrated in TransBase [3], a proprietary DB. However, I couldn’t find any open-source implementation of this structure.

B-Tree has an advantage over R-Tree as the basis of this curve: better filling and compact. Drawbacks: Most of the algorithms used are limited by processor. I decided to run a comparison using Tarantool: the focus was on read/insert speed, as well as memory consumption.

What was required for building in Tarantool?

I found simple implementations of this structure for 2-3 dimensions, but I wasn’t interested in small dimensions as I was keen to compare performance with R-Tree index. I chose the same maximum dimensions as with R-Tree in Tarantool, i.e. 20. To do that, I needed a bit array with support for some primitive operations: bit retrieval/alteration, shift, and OR/AND logical operations.

First, I was about to use a borrowed open source-implementation, but soon I realized that I didn’t need a general-use bit array: key length is always equal to 64, so some operations get significantly simplified. I wrote my own implementation. Instead of system memory allocation functions, I began to use special allocators implemented in Tarantool [4].

The heart of index is a set of algorithms for using Z-order curve: computation of Z-address (using special lookup tables), check of whether a Z-address belongs to the search area, and detection of the first entry in the search area starting from a specified point. Research publications describing these algorithms can be found on the Web. I implemented, debugged and optimized them. My plan was to store Z-addresses inside already implemented B-Tree used for the TREE index.

How data handling is arranged?

In the most general case, we have tuple. This is an array of data in message pack format. Ideally, it’s enough to isolate indexed fields, interleave their bits and insert address with a pointer to tuple inside B-Tree.

However, it all would be so easy if we dealt only with the type unsigned, where sorted bit presentations of numbers would correspond to sorted numbers in natural presentation. Signed whole numbers have one set of presentation rules, and floating-point numbers have another. It all had to be combined. Since we store Z-address separately from the data itself, it is possible to make any kind of transformation with our keys, the main thing is to keep the sorting order. This can be done through fairly simple bit manipulations. For instance, for signed whole numbers, the lead byte could just be inverted. For other types, there are similar transformations, though a bit more complex.

All numerical types fit into 8 bytes, so the size of the resulting key will be N * 8 bytes, where N is the dimensions of our space. What to do with strings?

A quite common situation in work with strings is the prefix search. The first 8 bytes of a string can be used as a key. If the string is shorter, it can be added with zeros. Support for strings imposes a fundamental limitation on our index: we lose uniqueness. Even when strings differ in the ninth byte, they still will look the same for the system.

Let’s look at the code.

API of an index comprises a set of methods. Let’s consider only the main ones: search and insert operations.

get — element search by the full key. It works only for unique indexes. Our index cannot be unique, so the function is replaced by a special generic version that returns the “Unsupported index feature" error.

replace — element insertion. Let’s review this in more detail.

static int

memtx_zcurve_index_replace(struct index *base, struct tuple *old_tuple,

struct tuple *new_tuple, enum dup_replace_mode mode,

struct tuple **result)

{

(void)mode;

struct memtx_zcurve_index *index = (struct memtx_zcurve_index *)base;

if (new_tuple) {

struct memtx_zcurve_data new_data;

new_data.tuple = new_tuple;

new_data.z_address = extract_zaddress(new_tuple,

&index->bit_array_pool, index);

struct memtx_zcurve_data dup_data;

dup_data.tuple = NULL;

dup_data.z_address = NULL;

int tree_res = memtx_zcurve_insert(&index->tree, new_data,

&dup_data);

if (tree_res) {

diag_set(OutOfMemory, MEMTX_EXTENT_SIZE,

"memtx_zcurve_index", "replace");

return -1;

}

if (dup_data.tuple != NULL) {

*result = dup_data.tuple;

z_value_free(&index->bit_array_pool, dup_data.z_address);

return 0;

}

}

if (old_tuple) {

struct memtx_zcurve_data old_data, deleted_value;

old_data.tuple = old_tuple;

old_data.z_address = extract_zaddress(old_tuple,

&index->bit_array_pool, index);

memtx_zcurve_delete_value(&index->tree, old_data, &deleted_value);

z_value_free(&index->bit_array_pool, old_data.z_address);

z_value_free(&index->bit_array_pool, deleted_value.z_address);

}

*result = old_tuple;

return 0;

}

What should be noted here?

From the index perspective, there is no update, delete, insert, and replace operations. Their whole logic is performed in this method, receiving the old and the new tuples, as well as mode, i.e. information on whether the index is unique or not. Our index cannot be unique, so no additional check is required, and tuple can be inserted at once.

Methods memtx_zcurve_insert and memtx_zcurve_delete_value are methods of the B-Tree which has been already implemented in Tarantool and are used in common TREE index. Unlike a common TREE, we store not just tuple but Z-address as well — interleaved bits of indexed parts. Function extract_zadress is responsible for this.

Method create_iterator: from Lua, we invoke this method in case of select and pairs.

static struct iterator *

memtx_zcurve_index_create_iterator(struct index *base, enum iterator_type type,

const char *key, uint32_t part_count)

{

struct memtx_zcurve_index *index = (struct memtx_zcurve_index *)base;

struct memtx_engine *memtx = (struct memtx_engine *)base->engine;

assert(part_count == 0 || key != NULL);

if (type != ITER_EQ && type != ITER_ALL && type != ITER_GE) {

diag_set(UnsupportedIndexFeature, base->def,

"requested iterator type");

return NULL;

}

uint8_t index_dim = base->def->key_def->part_count;

if (part_count == 0) {

/*

* If no key is specified, downgrade equality

* iterators to a full range.

*/

type = ITER_GE;

key = NULL;

} else if (index_dim * 2 == part_count

&& type != ITER_ALL) {

/*

* If part_count is twice greater than key_def.part_count

* set iterator to a range query

*/

type = ITER_GE;

}

struct tree_iterator *it = mempool_alloc(&memtx->zcurve_iterator_pool);

if (it == NULL) {

diag_set(OutOfMemory, sizeof(struct tree_iterator),

"memtx_zcurve_index", "iterator");

return NULL;

}

iterator_create(&it->base, base);

it->pool = &memtx->zcurve_iterator_pool;

it->base.next = tree_iterator_start;

it->base.free = tree_iterator_free;

it->type = type;

if (part_count == 0 || type == ITER_ALL) {

it->lower_bound = zeros(&index->bit_array_pool, index_dim);

it->upper_bound = ones(&index->bit_array_pool, index_dim);

} else if (type == ITER_EQ) {

it->lower_bound = mp_decode_key(&index->bit_array_pool,

key, index_dim, index);

it->upper_bound = NULL;

} else if (base->def->key_def->part_count == part_count) {

it->lower_bound = mp_decode_key(&index->bit_array_pool,

key, index_dim, index);

it->upper_bound = ones(&index->bit_array_pool, index_dim);

} else if (base->def->key_def->part_count * 2 == part_count) {

it->lower_bound = z_value_create(&index->bit_array_pool, index_dim);

it->upper_bound = z_value_create(&index->bit_array_pool, index_dim);

mp_decode_part(key, part_count, index, it->lower_bound, it->upper_bound);

} else {

unreachable();

}

it->tree_iterator = memtx_zcurve_invalid_iterator();

it->current.tuple = NULL;

it->current.z_address = NULL;

return (struct iterator *)it;

}

Depending on the provided key, we compute the lower and the upper request boundaries. However, this iterator points at nothing as yet. There are several types of iterators. In this case, it’s ALL — obtain all elements; EQ — obtain all elements whose Z-address matches the delivered one; and GE — a selection of elements in a hypercube.

destroy — delete index. When the index is secondary, the function frees up memory which was allocated to the search structure. And when the index is primary, it physically deletes stored tuples.

The whole code is available at https://github.com/olegrok/tarantool/tree/z-order-curve-index

Let’s see what we have as a result and draw conclusions.

space = box.schema.space.create('myspace', { engine = 'memtx' })

pk = space:create_index('primary', { type = 'tree', parts = {{1, 'unsigned'}}, unique = true})

sk = space:create_index('secondary', { type = 'zcurve', parts = {{2, 'unsigned'}, {3, 'unsigned'}}})

for i=0,5 do for j=0,5 do space:insert{i * 6 + j, i, j} end end

-- returns all tuples

pk:select{}

-- (2 <= x <= 3) and (3 <= y <= 5)

sk:select{2, 3, 3, 5}

---

- — [15, 2, 3]

- [21, 3, 3]

- [16, 2, 4]

- [22, 3, 4]

- [17, 2, 5]

- [23, 3, 5]

…

-- (x == 2) and (y == 3)

sk:select{2, 3}

---

- — [15, 2, 3]

-- (2 <= x <= 3)

sk:select({2, 3, box.NULL, box.NULL})

---

- — [12, 2, 0]

- [18, 3, 0]

- [13, 2, 1]

- [19, 3, 1]

- [14, 2, 2]

- [20, 3, 2]

- [15, 2, 3]

- [21, 3, 3]

- [16, 2, 4]

- [22, 3, 4]

- [17, 2, 5]

- [23, 3, 5]

...

-- (x >= 2) and (y >= 3)

sk:select({2, box.NULL, 3, box.NULL})

---

- — [15, 2, 3]

- [21, 3, 3]

- [27, 4, 3]

- [33, 5, 3]

- [16, 2, 4]

- [22, 3, 4]

- [17, 2, 5]

- [23, 3, 5]

- [28, 4, 4]

- [34, 5, 4]

- [29, 4, 5]

- [35, 5, 5]

...

What about performance?

Not so great, as it turned out.

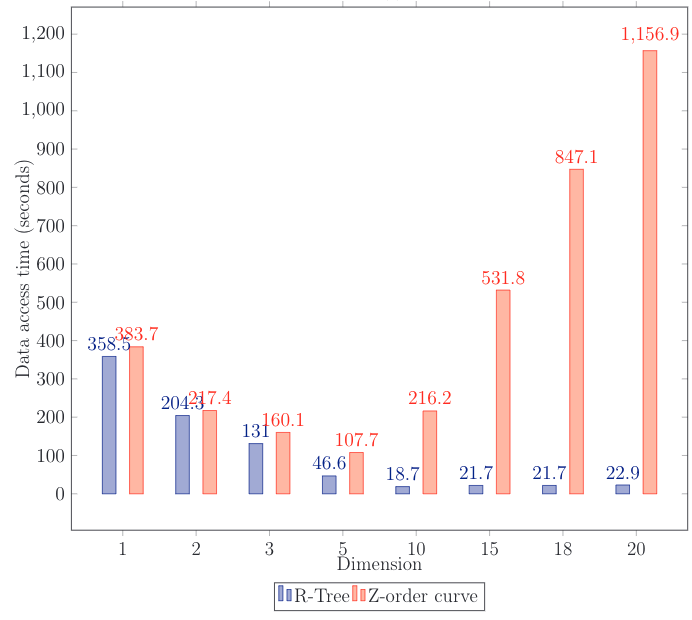

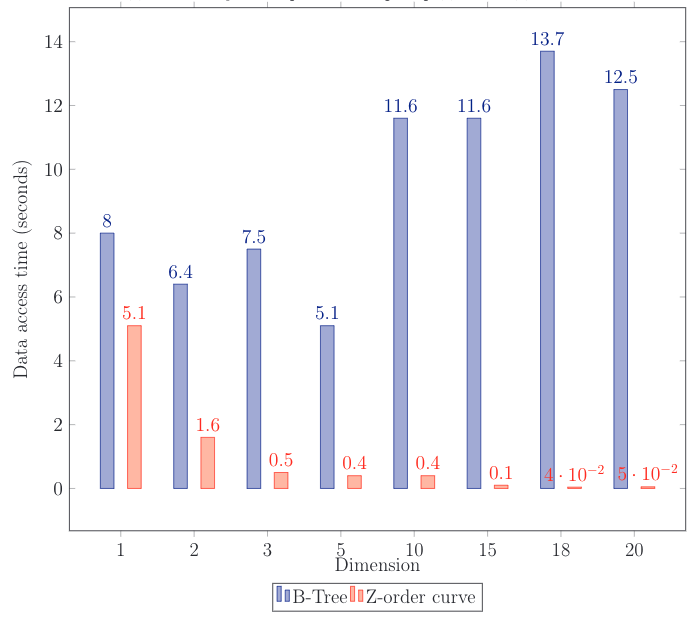

Starting from some point, the Z-order curve starts losing data access speed considerably. As shown by perf top, most of the time was spent on checking whether a point belonged to the search area, and on computing the next point to jump to. Both operations have linear complexity depending on the key length, i.e. length grows along with growing dimensions.

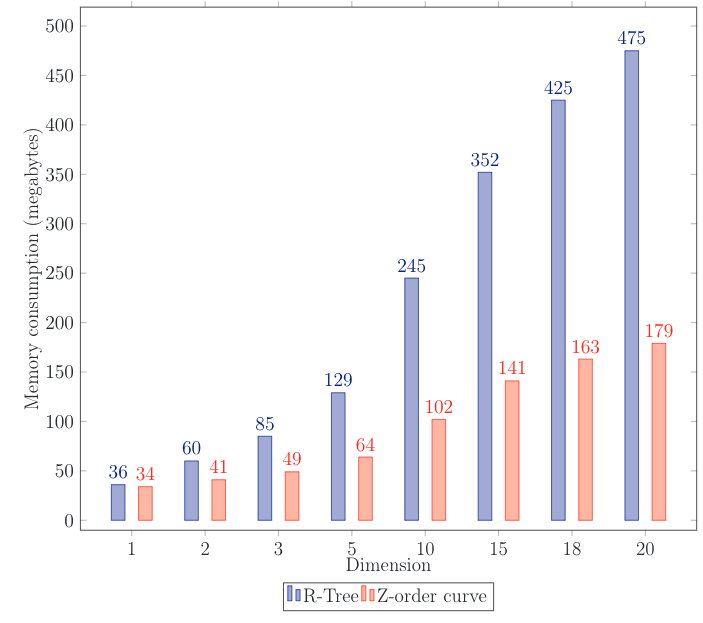

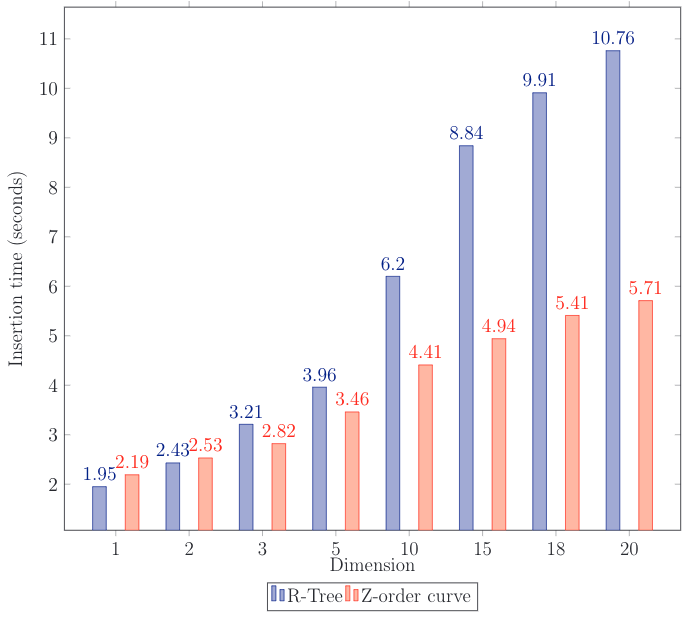

Good news: memory consumption is 2–3 times lower and insertion is slightly faster than with R-Tree. But the measurements were performed with disengaged WAL. In a production environment, disengaged WAL can lead to data loss in case of a fault. On top of that, although WAL writing uses a batch approach, it is still writing to disk, which is thousands of times slower than random access memory operation.

It is also interesting to compare to B-Tree. The curve turned out to be faster than total scanning and checking each point for belonging to the specified area. This is true even though the check is more light-weight than the Z-order curve where it all comes down to bit-wise comparison. Values on the graph differ by order from R-Tree: the test was slightly modified.

For the test, I generated a set of points and compared time length for request using Z-curve and for ordinary scanning.

Conclusions

The in-memory world didn’t bring out the best in this structure; however, it has some advantages:

- Takes less space.

- Typed, unlike R-Tree (relevant only for Tarantool).

- It makes sense to give it a closer look when only B-Tree is available, and multidimensional requests are required to be made (not relevant for Tarantool).

It was an exciting experiment. Although, the solution I proposed here would hardly become a part of Tarantool.

Sources:

[B-Tree]:

- Indexes PostgreSQL — 4 / Postgres Professional Blog / Habr

- B-tree / Habr

- B-Tree data structure / OTUS Blog. Online education / Habr

[ZcurvePostgres]:

Discussion

We invite you to our forum for discussion. You are welcome to use the widget below.